There was a time in my life when summers were synonymous with cinema. A time when central AC was a rarity at home, or at least in my house, and the only option to “stream” was to stay in the theater all day. Did anyone else do that? See a film, then immediately unpeel their feet from the sticky floor, get back in line, and watch it one more time? I know I did. Nothing was better than escaping into the cool darkness of Loew’s Pittsford Triplex on a sweltering afternoon and sinking into the worn velvet seats with a bucket of hot buttered popcorn.

Star Wars and ET. Caddyshack and Stripes. Grease. Fame. Fast Times at Ridgemont High.

Eventually, the final credits would roll, and my friends and I would emerge bleary-eyed into the blinding sunlight, waiting for our parents to pick us up on the hot pavement, already making plans to do it again. Those were the days.

So many summers spent off the coast of Maine have made such cinematic experiences beyond my reach, but this year, I was summoned back to the screen to see Oppenheimer. Not once, but twice.

I went with a purpose—not to escape but to excavate. Because Oppenheimer’s script is entwined with my story. Because my grandfather, Julian H. Webb, was one of the scientists who worked on the Manhattan Project.

Although many of the specifics have remained unspoken, I have always known that in the summer of 1944, my grandparents and father quietly relocated to Oak Ridge, Tennessee. My grandfather would be a manager of the Y-12 Lab, my father, a fourth-grade student, and my grandmother would tend to the home they were assigned in a guarded “secret city.”

There is a scene in Oppenheimer when the amount of refined uranium needed for constructing the atomic bomb is measured as marbles in a fishbowl. The Y-12 Lab separated the uranium, thus “making” the marbles. According to my father, he remembers being (later) told that the uranium was transported across the country by train, in briefcases handcuffed to members of the military, and then delivered to Los Alamos. From one secret city to another.

In 2023, the concept of a single unmapped, secret city is unimaginable—let alone three. What was it like for my father to unexpectedly move from Rochester to Tennessee to start school on an army base or for the wives, including my grandmother, to do their best to maintain a normal life, as they were equally isolated from all that was familiar? To know a question like “What did you do at work today, dear?” could never be answered until August 6, 1945, let alone for the scientists who lived with the magnitude of knowing that the most significant scientific creation of their careers came at the cost of death and destruction to so many more.

My grandmother was a 1940s housewife; she did what she was told. I remember her telling me that when they moved to Oak Ridge, she asked the officers if their Type D home could be painted yellow, her favorite color.

"Mrs. Webb, you'll get whatever color they've given to us."

Their alphabet house was not yellow.

My father can’t recall if they brought their furniture with them or not; there are no photographs we can find. He does remember that their house backed up to the edge of a forest, where he spent hours hunting with a bow and arrow.

If I’m honest, regardless of my heritage, my understanding of life does not come through the lens of math or science. A numerical equation on a chalkboard looks no different to me than a Cy Twombly painting; both are exquisite, but one has nothing to do with the other.

The first time I saw Oppenheimer, I was looking for answers, but to what, I am no longer sure because Los Alamos was not Oak Ridge, and the story of the Manhattan Project is so much more than the story of scientists and the making of the atomic bomb. And here, dear reader, is where this essay became a (k)not of unknowing in my mind for weeks on end. I may never be a theoretical physicist, but I will forever be an overthinker, even when it takes me down. This was one of those times.

As I wrote and wrote (and wrote) about what I thought I knew—forcing the film through the lens of tantra, dharma, and the Bhagavad Gita, I became lost in a black hole which, while an extraordinary way to consider Oppenheimer, had nothing to do with my ancestry or the story I wished to explore.

It was time to begin again.

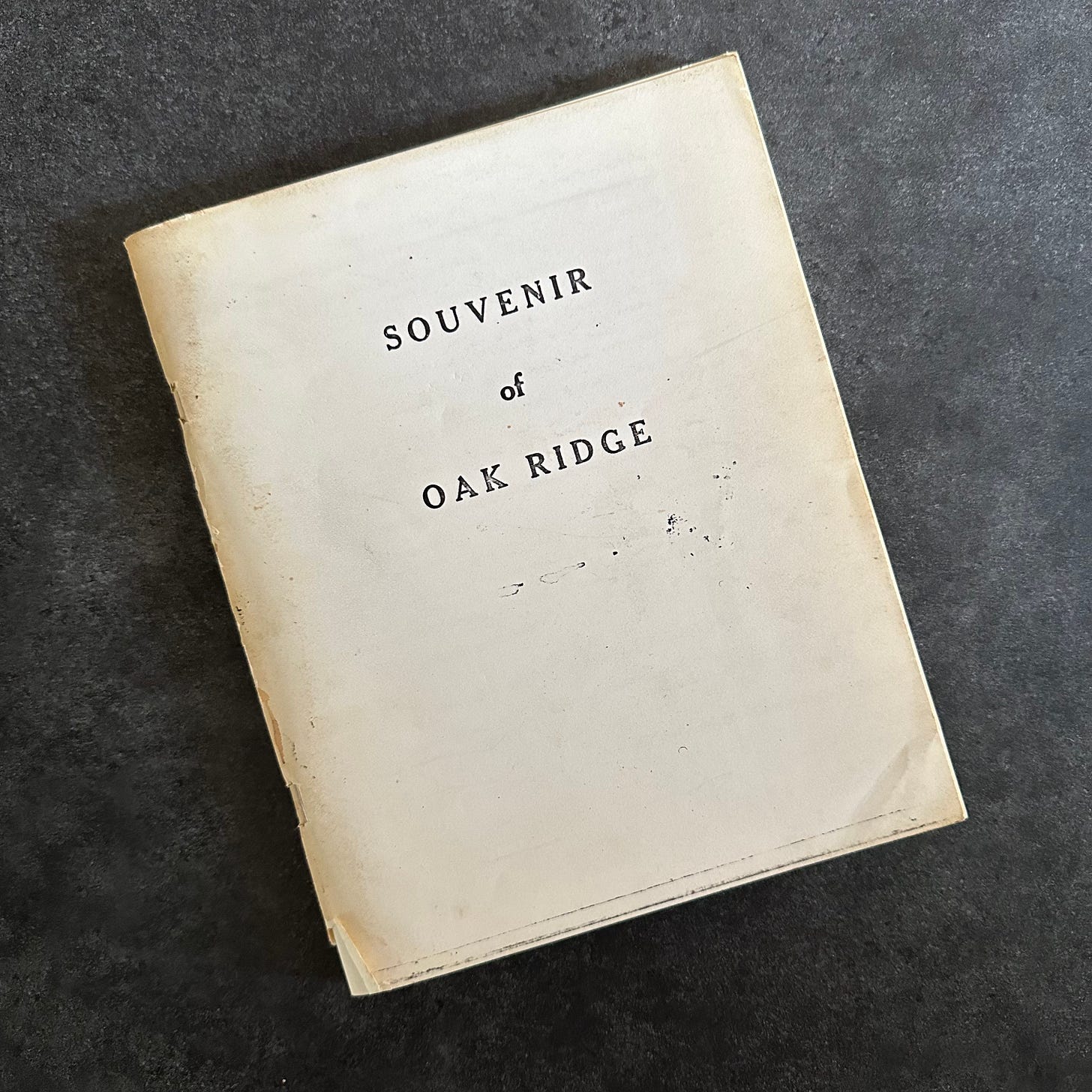

Last Saturday, I returned to the theater for a second screening, and in the darkness, I finally saw the story I wanted to tell, the one that had been there the whole time, the one about my Grandmother and a cookbook, her Souvenir of Oak Ridge.

Sixty-two sheets of legal paper folded and stapled through the spine. I never gave it much thought, but I must have become the recipient (along with multiple boxes of handwritten recipe cards) when we emptied my grandparents' house, and I've carried it with me ever since.

Inside the cover, it reads:

This is the offering of a small group of Oak Ridge friends - gathered from the hostesses of informal parties, coffees, luncheons, teas and dinners. Many of the recipes are reminiscent of the pioneering days, during the first few months of the Atomic City and all are from the four corners of the United States. We hope that here you will meet some of your friends and enjoy their favorite recipes so graciously given.

Collected by Grace Werley with the kind assistance of Nell Flanary, Dot Hopkins and Charlotte Hood.

And then the recipes. Page after page, each identified by a woman’s full name and her home of origin: Massachusetts, Michigan, New York State. Rhode Island, Virginia, Ohio. California, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, the list goes on and on.

We do not need souvenirs of events that are repeatable; rather we need and desire souvenirs of events that are reportable, events whose materiality has escaped us.1 Every recipe in the cookbook is an act of resistance from a secret city and the trace of a woman’s authentic experience and authorship defiantly whispering, “We (too) were here.”

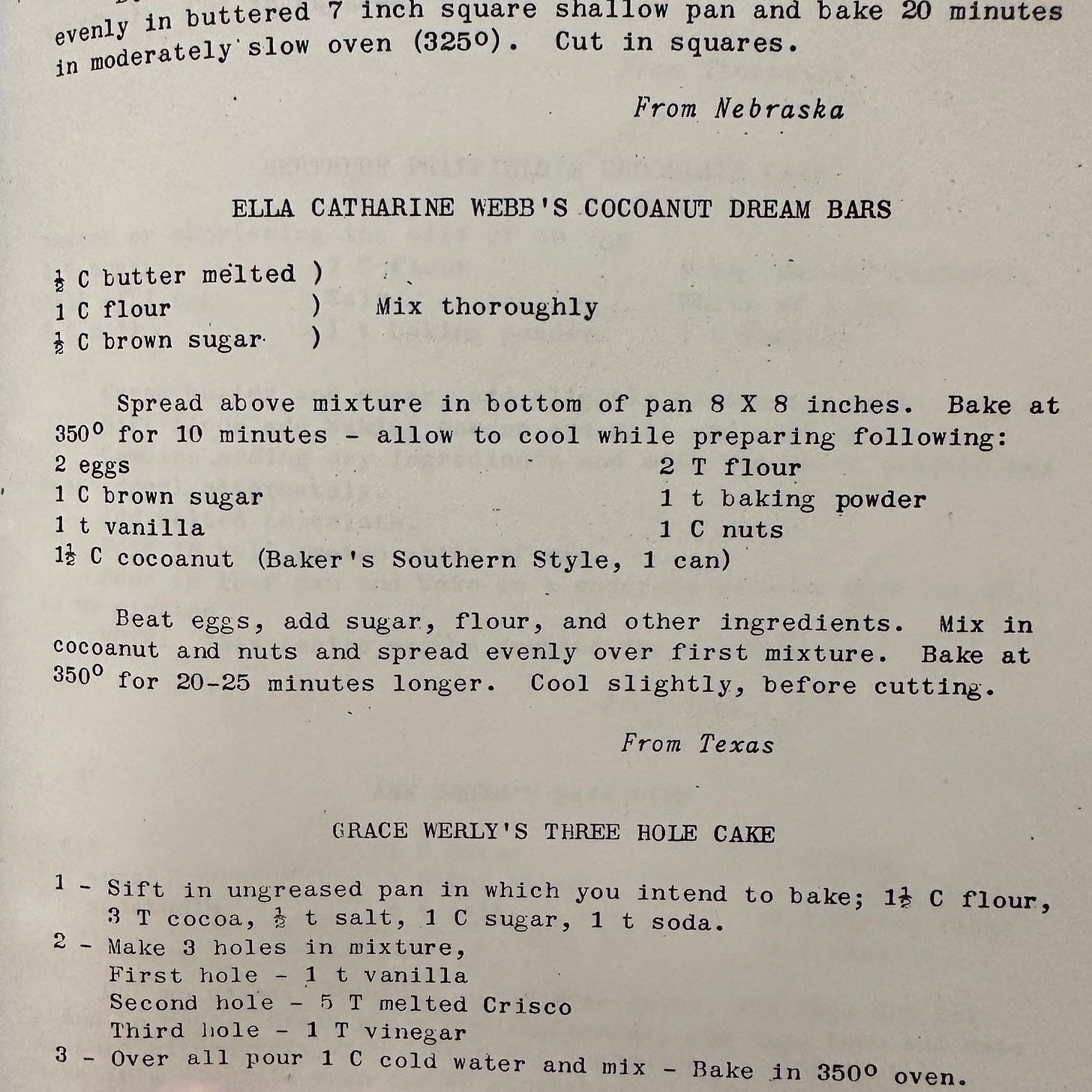

Tucked in between Alta Hull’s Brownies and Grace Werly’s Three Hole Cake, I found my grandmother’s contribution, Ella Catharine Webb’s Cocoanut Dream Bars.2

Early in the film, there is a conversation between Niels Bohr and Oppenheimer about theoretical physics. Bohr asks the young scientist,

The important thing isn't can you read music, it's can you hear it. Can you hear the music, Robert?

Yes, I can.

Throughout my life, I've held a similar affinity towards recipes—the ability to read a list of ingredients and taste the possibilities before proceeding. As others might immerse themselves in a novel, I can get lost in a cookbook, then approach my time in the kitchen with curiosity—relying on intuition and memory more than exact measurements, always willing to adjust and adapt accordingly. The question I always return:

Is what I'm about to make something I can imagine serving myself or others?

Two-thirds of the way through the film, Oppenheimer is asked a version of the same question by a roomful of scientists discussing the morality and the necessity of using an atomic weapon following Hitler’s suicide.

We imagine a future, and our imaginings horrify us. They won't fear it until they understand it, and they won't understand it until they use it.

At its inception, a recipe is merely a theory. It is a list of ingredients, followed by specific instructions with an assumed outcome. We don’t know how a recipe will taste until we make it. We can theorize, but theory only takes us so far. Because not all recipes, no matter how beautifully written, succeed, or at least in the ways we imagine, and not all recipes stand the test of time. Our tastes and our tolerance can change for specific ingredients or methods.

And perhaps some recipes should never be made at all.

Oppenheimer’s duty was to the physics; his task to test the theory. While he may have felt the atomic bomb was necessary at its inception, he had to live with the consequences of his actions; he recognized how his calculations created a chain reaction that destroyed the world we knew to be. Oppenheimer ultimately became a vehement opponent of pursuing a bigger bomb, the H-bomb.

Because once was more than enough.

There are many recipes in the cookbook I would never make once, let alone twice—it would be an understatement to call them unappetizing:

“Cheese It” Salad, Pressed Chicken, Dunk Butter, GLOP, Pineapple Sherry Mousse, Tomato Aspic Salad, Jefferson Davis Pie.3

But others might bear testing, say the above-mentioned Grace Werly’s Three Hole Cake. It feels like a definite no at first glance, but swap out a few ingredients, such as butter for Crisco, add a good balsamic vinegar, Dutch process cocoa powder, and Madagascar Vanilla, and you might be onto something. There is still the minor detail that Grace doesn’t say how long to cook the cake, but I’d start at 20-25 minutes and take it from there.

I have zero recollection of eating my grandmother’s Coconut Dream Bars, but I was often a finicky child, preferring Pepperidge Farm Frozen Rich Golden Layer Cakes served on a styrofoam tray. A part of me wonders if she ever made them because my father doesn’t remember them either. Perhaps, like her entire experience at Oak Ridge, the recipe is more of a memory, written, caught, and held in time like a dream of its own.

Still, I decided to give them a try.

Ella Kathryn Webb’s Coconut Dream Bars

•

Mix thoroughly:

1/2 c butter, melted

1 c flour

1/2 c brown sugar

•

Spread in the bottom of 8x8 in pan. Bake at 350 for 10 min ~ allow to cool slightly while preparing the following:

•

Beat 2 eggs

Add 1 c brown sugar, 1 t vanilla, 2 T flour, 1 t baking powder.

•

Mix in 1 1/2 c sweetened coconut flakes, 1 c chopped nuts

•

Spread evenly over first mixture. Bake at 350 for additional 20-25 minutes. Do not over bake. Cool before cutting. Yield 16 bars.

In making the recipe, a few adjustments were necessary. Instead of a can of Baker’s Southern Style Cocoanut, which no longer exists, I substituted sweetened coconut flakes, and while my grandmother doesn’t specify what sort of nuts, I opted for pecans because they were her favorite. She gave me a bag in my Christmas stocking each year. I made the recipe again with walnuts, and it was equally good. My grandmother didn’t top her recipe with whipped cream, but I’m sure she would approve.

When I took the cookbook off the shelf and read the recipes left behind, I began to discover what I was seeking. Clues. I noticed that my grandmother identified herself as being from Texas and not Rochester, as many other women did. But this makes sense as she was always fiercely independent, determined to make her own way. Perhaps that was her way to differentiate herself, even in a secret Atomic city.4

In making her Dream Bars, I honor the experience of a time when strangers came together in service to something greater than their own self-interest. With each bite, I taste the fullness of their stories. The ways they are remembered, (re)collected, and told. I went to see Oppenheimer in search of a story, but movies are merely a beginning—they can only tell us so much. What I hoped to find had been graciously given and in my home the entire time. My grandmother’s cookbook is her legacy, my Souvenir of Oak Ridge.

I’m curious—has there ever been a time when your family history intersected with larger events? What have you discovered along the way? And if you want to know more about any of the recipes (appetizing or otherwise), leave me a message in the comments ~ thanks for reading!

UPCOMING ~ SAVE THE DATE!

The Hidden Heart Retreat • February 1-4, 2024 • Finger Lakes, NY

Join Heidi Kroft & Sarah Webb for a weekend of discovery as we listen to our heart whisperings in beauty and bravery through yoga, meditation, and creative journaling.

if you enjoy this newsletter i’d love it if you spread the word or click the ♥️ and leave a comment so we can get to know one another in community. my deepest gratitude to all who are already sharing, liking, recommending, and restacking narrative threads: from breath to pen

oh! i’ve also been fiddling around with Substack Notes, and would love for you to join me there! in between my newsletters, i’m using it as shorthand space to share, and i’ve met the most wonderful people!

Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993, 135.

The proper spelling of my grandmother’s first name is Ella Kathryn.

Out of respect, I am choosing not to identify the contributors.

I’ll never know, but I have another theory about claiming Texas as her origin state because, on page 14, there is an almost identical recipe for Bea Roger’s Cocoanut Chews (also from Rochester, NY). Bea and my grandmother knew each other from the bridge tables, and my grandmother, who was a competitive Master card player, may have wished to create distance between their two recipes.

I love that (about Kissinger).

My mother was briefly engaged to Bruce McCandless, NASA astronaut who completed the first untethered space walk in 1984 and was the voice of Mission Control for the first lunar landing.

Again, may I stress that I am not a scientist? When it came to my senior HS physics exam I did the math and determined as long as I got a 28 I could graduate, so instead of studying I went to the premiere of Ghostbusters ~ I think I got a 57??? 🤦♀️

Sarah. What an exquisite, poignant story you’ve sewn. The dreamy imagery of recipes as memories. And I’m fascinated by the Secret City. More, I hope, will be revealed.